Like many people, the first time I saw Billy Preston was on “Let It Be,” and his luscious electric keyboard noodle on “Don’t Let Me Down” and “Get It Be.” It provided a great center for songs such as “Back”. But it wasn’t until George Harrison’s trendsetting rock concert film The Concert for Bangla Desh, released in 1972, that I realized who Billy Preston really was. It was. For most of the benefit concert at Madison Square Garden, Preston was in the background tickling the plugged-in ivories. But then, with Harrison’s introduction, he performed his 1969 single “That’s the Way God Planned It”, which he recorded for Apple Records. It stood out from the rest of the show as dramatically and masterfully as Sly Stone’s performance of “I Want to Take You Higher” at Woodstock.

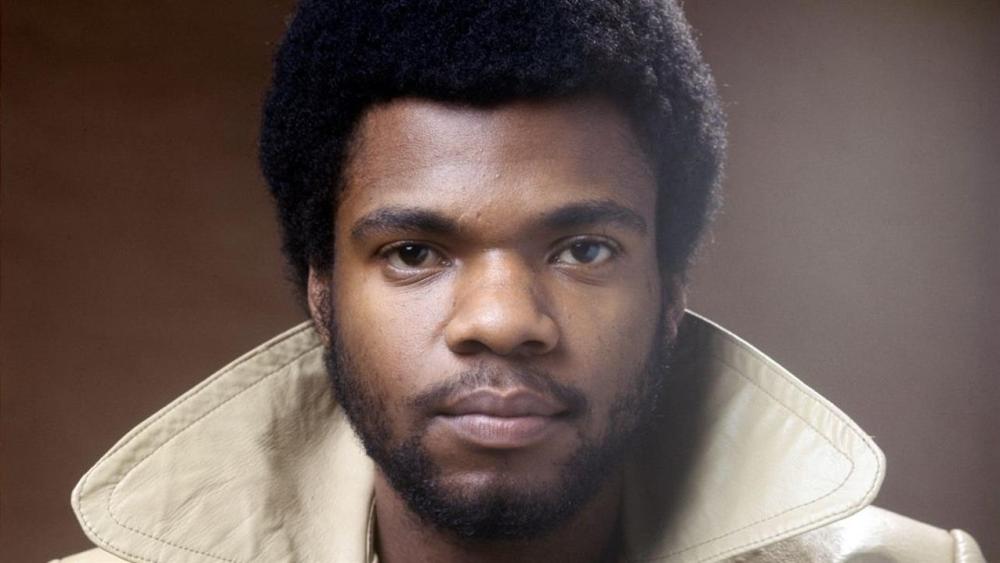

The sound of a sacred organ rang out, and the camera zoomed in on a stylish man with a big woolen hat and a Billy Dee Williams-like mustache, a neat gap-toothed grin and a radiant sense of respectability. . he started singing (“Why can’t we be humble, as the good Lord said…”) and it sounded like a hymn, but it was just a rock’n’roll hymn. The lyrics were uplifting, and Preston caressed each rhythm as if he were leading a gospel choir. In 1971, how many pop songs could you name that had “God” in the title? (There was “God Only Knows,” but…that’s about it.)

But when he enters the chorus with a delicate descending chord, the bassline continues in tandem, at least until the climax, when that bass begins to wander around as if it has a mind of its own, and the song takes off. I could feel it starting. …will rise. Preston, rocking back and forth, head tilted in glee, notes pouring out of him like sun-kissed honey, was the only black performer on that stage, and he rocked. It presented what amounts to a radical message in the world of : it was god here. As the song sped up in the gospel tradition, Preston, moved by the spirit he was evoking, got up from his keyboard and began dancing, arms jangling and legs almost floating. It was an ecstatic dance that seemed to come out of him, as if he couldn’t stop himself.

Paris Barclay’s eye-opening documentary Billy Preston: That’s the Way God Planned it opens with that sequence, but watching it again is cathartic. The “Concert for Bangladesh” had three highlights. The way George Harrison walked off the stage felt like one of the coolest things I’d ever seen when I was 13 years old. middle The final praise of the song “Bangladesh”. And Billy Preston’s performance. I looked at it and thought, “Who is this guy?” And he said, “I need to see more.”

But as the documentary reveals, Billy Preston was an elusive figure – feisty, yet hidden and mysterious. His career was like that too. He was a genius session musician who worked with Little Richard, Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin, Sly Stone, the Rolling Stones, and of course the Beatles. During the “Get Back” sessions, he effectively added To the unprecedented Beatles. (A scrapbook montage near the beginning of the film shows a magazine headline: “Fifth Beatle Is a Brother.”)

As the ’70s progressed, Preston released several pop-funk singles that people still remember fondly, including “Will It Go Round in Circles” and “Nothing from Nothing” did. This song was performed on the first episode of the TV show “Saturday”. Night Live,” she said, smiling under a head-long Afro wig. But given his talents (keyboard virtuoso, strong soul voice, excellent dancer, ability to create propulsive hooks), why didn’t Billy Preston become a bigger star? Who was he as an artist? I went into the documentary feeling vague about all of this, but I felt like I finally got to know him.

That includes getting to know the side of him that drew him in. Preston was gay, as most people around him eventually realized, but was extremely secretive and conflicted about it. Was he suffering internally, like Little Richard, with whom Preston toured in the early ’60s? Little Richard was the most colorful hidden figure in rock history…until he gave up music for the church…then returned to the world of pop and came out of the closet…then re-entered and denounced homosexuality. I did…and repeated it. it is It was contradictory.

Preston had a gentle personality, and it’s hard to know whether his relationships, which he kept hidden (sometimes showing up on private planes saying he was traveling with his “nephew”), caused the inner stress. . However, he was raised in the church by a single mother, remained tied to the church, and had no desire to publicly declare who he was. Billy Porter, interviewed in the film, explains the history of the affair (“It’s not just choirmasters, honey. There’s plenty of queens in everyone’s church”) and why it hasn’t been talked about. I’m talking about Tanaka.

Preston had musical The connection to the black church was unique and almost primitive in the rock world. He played the organ, especially the Hammond B3, a complex instrument with multiple levels. (He was also a Fender Rhodes wizard.) Great books will be written or documentaries made about the use of organs in pop music (“A Whiter Shade of Pale,” “Like a Rolling Stone”, “Like a Rolling Stone”). “Green Onions,” “Let’s Go Crazy,” “In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida,” Boston’s “Foreplay,” Blondie’s “11:59”), and Billy Preston is just shy of that instrument. He was a king without. Born in 1946, he started playing the song in church at an early age, but it quickly became a crossover phenomenon. There’s an amazing clip of him on “The Nat King Cole Show” in 1957, where he performs a song he wrote called “Billy’s Boogie,” and his jovial confidence is astounding. There is something to keep an eye on.

But here’s where it gets amazing. Starting in 1963, Preston released a series of three albums centered around organ playing. The third, “The Wildest Organ in Town!” (1966), was a collaboration between Preston and Sly Stone, who arranged the song but did not write the music. One of the tracks, “Advice,” is clearly a precursor to “I Want to Take You Higher.” The inventor of funk was James Brown, and the two inheritors and innovators of the funk myth were Sly Stone and George Clinton. But the documentary makes the case that Billy Preston created a huge part of funk’s DNA. His influence is evident from the 1971 single “Outa-Space,” which became the prototype for a kind of clavinet-driven ’70s jam (the Commodores song “Machine Gun” featured on “Boogie Nights”) is just a remake of Boogie Nights) it).

Preston was successful and enjoyed the fruits of his labor, as did his horse ranch in Topanga Valley. He was revered by people like Mick Jagger who performed Preston on stage – how many people could dance? and Mick Jagger? — on the Stones’ 1975 tour. However, if Preston had pursued his career differently, he might have become a more popular artist, perhaps the leader of a big band like the Commodores or Kool and the Gang. I think it’s clear that it could have happened.

But it’s also possible that his association with the mainstream rock world hurt him. His identity as a black artist became blurred at a time when such categories were strictly enforced by culture. (He was accused of being a prostitute in the same way as Whitney Houston.) In another, Preston’s identity remains ambiguous, and this is not a withdrawal rooted in the concealment of his sexuality. It is related to the tendency that did not occur. Was he a sideman or a star? The only way to be a star is to chase it hard enough, and there was still a part of Preston that was more comfortable standing in the shadows. .

Just when you think you’re watching a light-hearted pop doc, the darker side of Billy Preston’s life intrudes upon you. And will it be dark forever? Early in the film, Billy claims that he “lost his virginity” during a tour with Little Richard in 1962, when he was just 16 years old (it was on that tour that Preston hung out with the Beatles at Hamburg’s Star Club). inside). But according to Preston’s friend and noted rock biographer David Ritts, he never talked about his childhood experiences. Did something happen between him and Little Richard? This movie suggests that possibility.

And guess whatever trauma Preston experienced as a church-raised teenager on the streets with depraved rock and rollers, it came back to haunt him in his self-destructive abuse of alcohol and cocaine. But you don’t really need to connect the dots. . This chapter of the story begins rather abruptly, but once it does, Preston’s end is tragic.

He couldn’t stay off cocaine. Or, once the cocaine arrived on the scene, it just couldn’t leave. He defaulted on millions in taxes and racked up a mountain of debt. His career bottomed out in the late ’70s, when disco evolved black music beyond Preston’s funk-based grooves. And he never had a solid home life to act as a stabilizer. He became the bandleader on David Brenner’s short-lived talk show, but in a lurid incident, Howard Stern, a guest on that show, came up to Preston, smelled booze on his breath, and called out to him. There is a clip like this. I remembered that he was a man who once performed with the Beatles. Mr Preston died in 2006 at the age of 59 after battling kidney disease worsened by drug use. But he left behind a trail of people who worshiped him. And when you look at his talent, the gentle glow of his presence, the way he sweeps you away with one organ riff and perhaps blasts you skyward, there’s no doubt that Billy Preston has waxed and waned. You can say that. Not the way God planned.