One of the most fascinating characters in Ondi Timoner’s 2022 documentary The Last Flight Home, about 92-year-old father Eli Timoner’s decision to take advantage of California’s end-of-life options, is It was the director’s sister Rachel. . Rabbi Rachel Timoner brought pastoral warmth and spiritual insight to the sorrows and joys, rituals and spiritual counting of families as they honor the passing of a loved one.

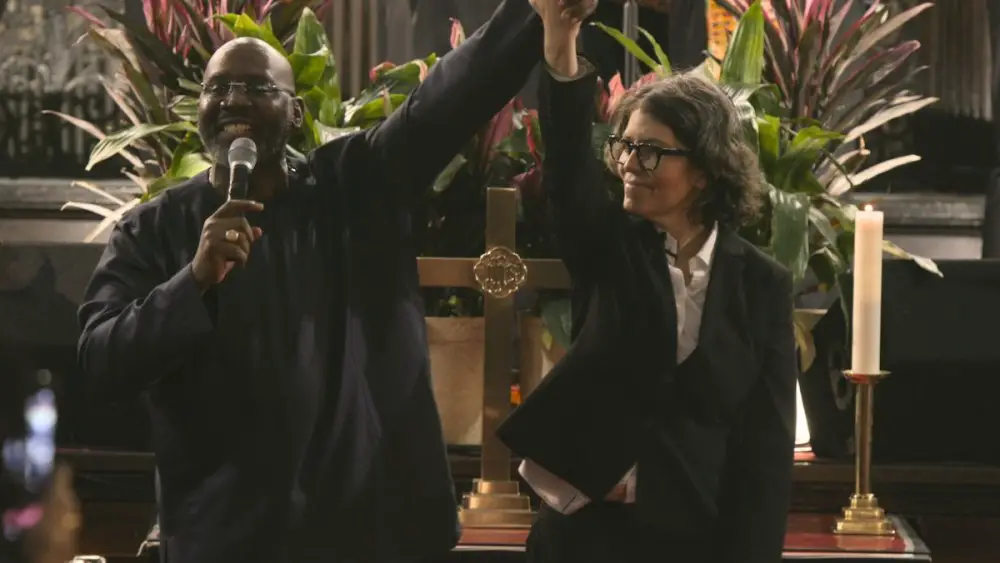

Now, in “All God’s Children,” Timoner takes a positive but emotionless close-up of his sister. However, this documentary is not a family memoir. Instead, Rachel Timoner, senior rabbi of Brooklyn’s historic Beth Elohim Congregation, will be joined by the Rev. Robert Waterman, senior pastor of the also historic Antioch Baptist Church in Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuy neighborhood. and share the top salary.

Although the two institutions are just four miles apart, their leaders aim to cross the wider divide of racism and anti-Semitism. “All God’s Children” depicts this Jewish woman and this black man trying to bring the congregation together in worship, but it doesn’t go smoothly. That’s what makes this frank film so important and instructive.

The two leaders are similar in age and reputation. Sen. Chuck Schumer attends Beth Elohim. Congressman Hakeem Jeffries visited Antioch. So does New York Attorney General Letitia James. Each has a unique sensibility. (“God is beyond gender,” the rabbi tells a class of schoolchildren.) It is no surprise that these two embark on a journey toward deeper understanding. What seems strange at times are events that threaten to tear apart their budding relationships and upend their quest for communal harmony. As one Antioch parishioner put it, “Love unites us, but tradition separates us.” His assessments have proven to be accurate time and time again.

It touches on the history of Black and Jewish migration to Brooklyn and illuminates the implications of the involvement of two distinct diasporas. Pogroms and slavery, the Holocaust, and the Red Summer that devastated Tulsa’s black community are reflected in familiar and still heart-wrenching photographs and newsreel footage.

When the film was released in 2019, Black residents of Bed-Stuy were victims of “deed theft.” This predatory practice allows third parties to take ownership of a home without the owner’s knowledge, purchase the property, and evict the actual owner. It had become a tool of aggressive gentrification. And despite its name, it was not illegal in New York. Given Brooklyn’s demographics, some of the landlords and real estate agents involved in this act were Jewish. Almost all of the injured were black or brown residents. Rabbis and preachers had good reason to reach out.

When Antioch parishioners visit CBE (as it is affectionately called by the congregation) for the first time, the musical performance by the visitors includes flag waving. The bright yellow one has “Jesus” written on it. A seemingly innocent incident sends Rabbi Timoner and his second, Stephanie Collin, into a frenzy of worrying whispers. “Should they say something or should they do something?” Timoner would later speak at a gathering of participants from both places of worship, which was a bit of an event. .

Still, they all persist, and after the flag incident, the congregation goes on a joint field trip to the National Museum of African American History and Culture and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. And while there is a common recognition of the trauma rooted in history, the hurt and alarm from the flag incident has not completely disappeared.

Over the course of the film, each congregation visits the other’s place of worship during Passover and Easter celebrations. CBE’s seder goes off without a hitch, aside from a few particularly bland matzah balls. But when the Antioch service includes a theatrical reenactment of the story of Christ, with its trial, crucifixion, and resurrection, things get even worse than the flag incident. “Should I leave?” Timoner asks fellow rabbi Stephanie Collin, who sits miserably in the pew.

Of course, there are many things that I don’t understand. Reading the annual Passion Play of Antioch strictly within the context of Europe’s long tradition of anti-Semitism and “blood libel” reveals how the story of God’s love is reflected in the enslavement of America. We may miss examples that resonate more with the people of Moses, such as how they became entrenched in the lives of black people. .

Things get so tense that a mediator skilled at leading discussions about anti-Semitism and racism is called in. She travels many times from Kansas City, Missouri to Brooklyn.

As the hardships continue, viewers naturally wonder what possessed Timoner and Waterman to begin a journey that focuses so deeply on religion, an ancient and ongoing source of antagonism. , it’s natural to wonder. “Maybe starting with worshiping together was the wrong first step,” Timoner says, a little embarrassed.

But then, as the film moves toward its conclusion, which includes last October’s terrorist attack by Hamas and the killing of thousands of Palestinians by the Israeli government, if the film had It is difficult to imagine that they had such deep feelings for each other. It’s not about confronting those mistakes. There are lessons to be learned, and the film makes a compelling case that at least two Brooklyn congregations and their leaders have much practical wisdom to share.